How I Found My Audiobook Narrator

I’ve been an audiobook addict for years. I listen to an average of two books per week while commuting or doing housework. As someone with the equivalent of two full-time jobs, multitasking with audio is the primary way I experience books. If they weren’t mine, I wouldn’t have time to read my own epic novels!…

Anatomy of a Book Cover, Part 2

Are you ready for the real designer wizardry? To quote Desdemona in Othello: “O, these men, these men!” The male characters on the ebook covers of Necessary Sins and Sweet Medicine were particularly challenging to represent with stock images. No single image would do; my cover designer, Damonza, had to combine multiple images and make…

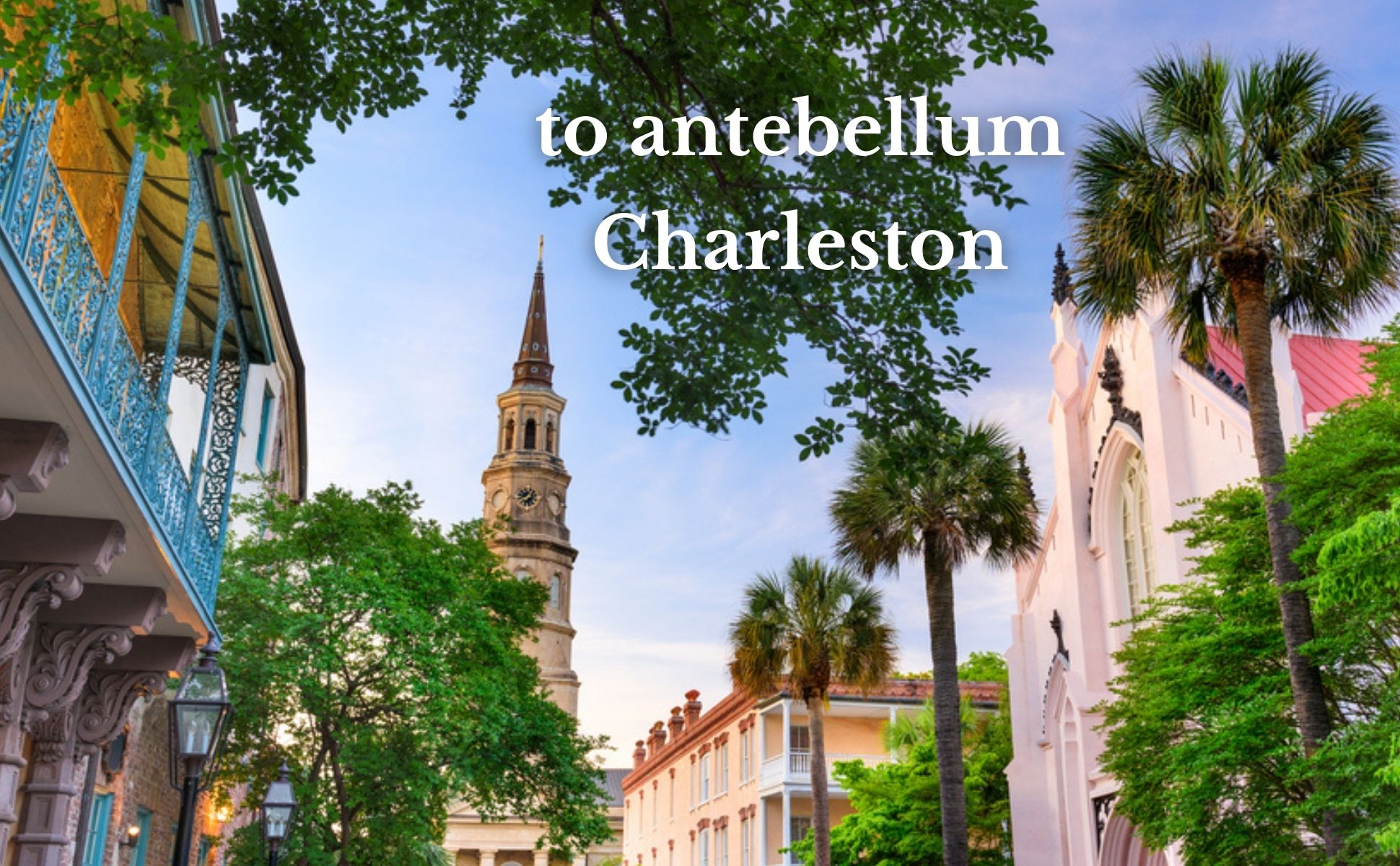

Anatomy of a Book Cover, Part 1

After five months of research and revisions, the ebooks of The Lazare Family Saga have brand-new covers at last! If you’re curious why and how they look the way they do, make yourself comfortable. The creation of these four covers for my fictional family saga is a saga itself, so I’ve split it into two…

On Second Thought…

“Ring out the old, ring in the new…” — Alfred, Lord Tennyson, In Memoriam (1850) In November-December 2021, I completed a new edit of the entire Lazare Family Saga. I am a perfectionist; I could honestly go through these long books every year and find things to change. But I shall endeavor to be satisfied…

Necessary Sins Has a New Cover!

Why I changed the cover of my debut novel Necessary Sins and what’s on the horizon

Do I Get An A+?

Firstly, I am thrilled to share that Amazon.com selected Necessary Sins, the first book in my Lazare Family Saga, as one of their Prime Reads for the months of September, October, and November 2021. If you’re a U.S. member of Amazon Prime, that means you can read the Kindle edition of Necessary Sins for free…

What I’m Working On Now

Now that I’ve published all four books in my Lazare Family Saga, I’ve had interviewers and readers asking about my next project. My answer will disappoint many. It disappoints me too. I wish I had the luxury to write full-time, to dive into something new. The reality is, I do not. My time and energy…

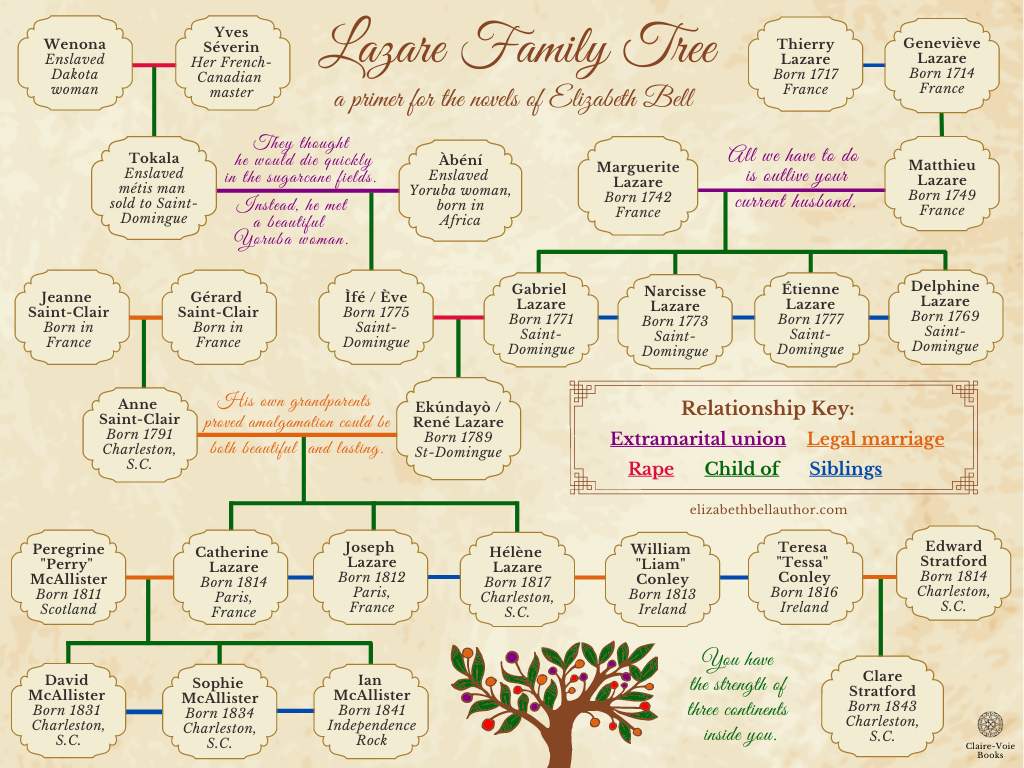

A Lazare Family Tree

If you’ve found yourself reading the Lazare Family Saga and trying to remember just how Character X is related to Character Y, you’re in luck! Using Canva, I created this handy color-coded family tree, which hopefully looks a little bit like it was painted on parchment. When I thought I’d be attending the 2021 Historical…

The Sweetest Medicine

The title of the fourth and final book in my series, Sweet Medicine, used to be the title for the whole story, back when I thought that story was a single novel. I like the phrase because it’s a seeming oxymoron—a pattern I ended up using for all my titles. How can medicine be sweet?…

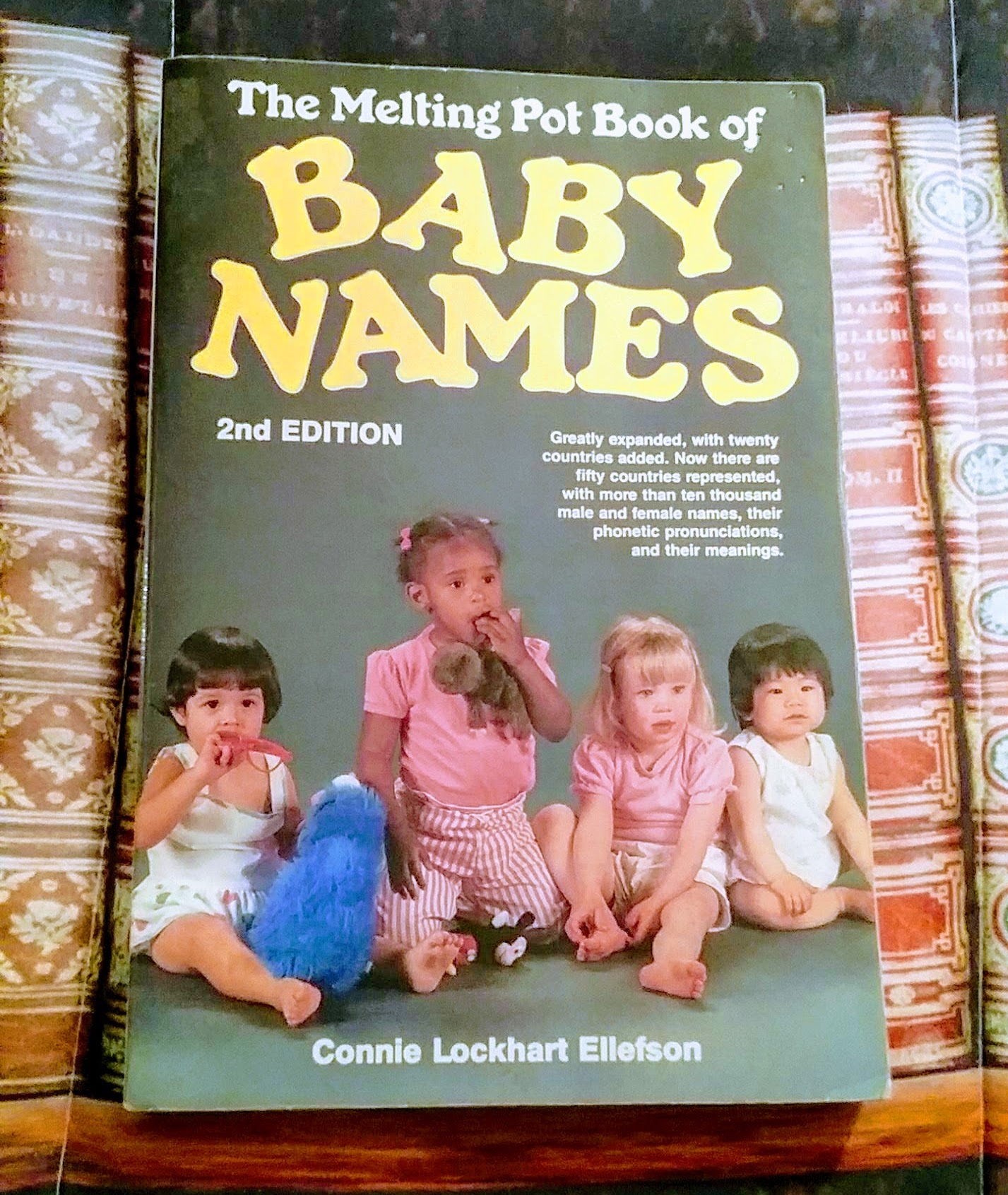

What’s in a (Character) Name?

In Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare famously wrote: What’s in a name? that which we call a roseBy any other name would smell as sweet;So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d,Retain that dear perfection which he owesWithout that title. But he gave those words to a lovestruck teenager. I suspect Shakespeare himself felt differently,…

End of content

End of content