The Language of Flowers

Like many a 19th-century novelist, I use the Language of Flowers throughout the Lazare Family Saga as part of my symbolism. I explain some of this floral code in my books, while other references are “Easter eggs.” In this post, I’ll unpack some of those meanings, and I’ll include illustrations in case the word “anemone”…

My Creative Process

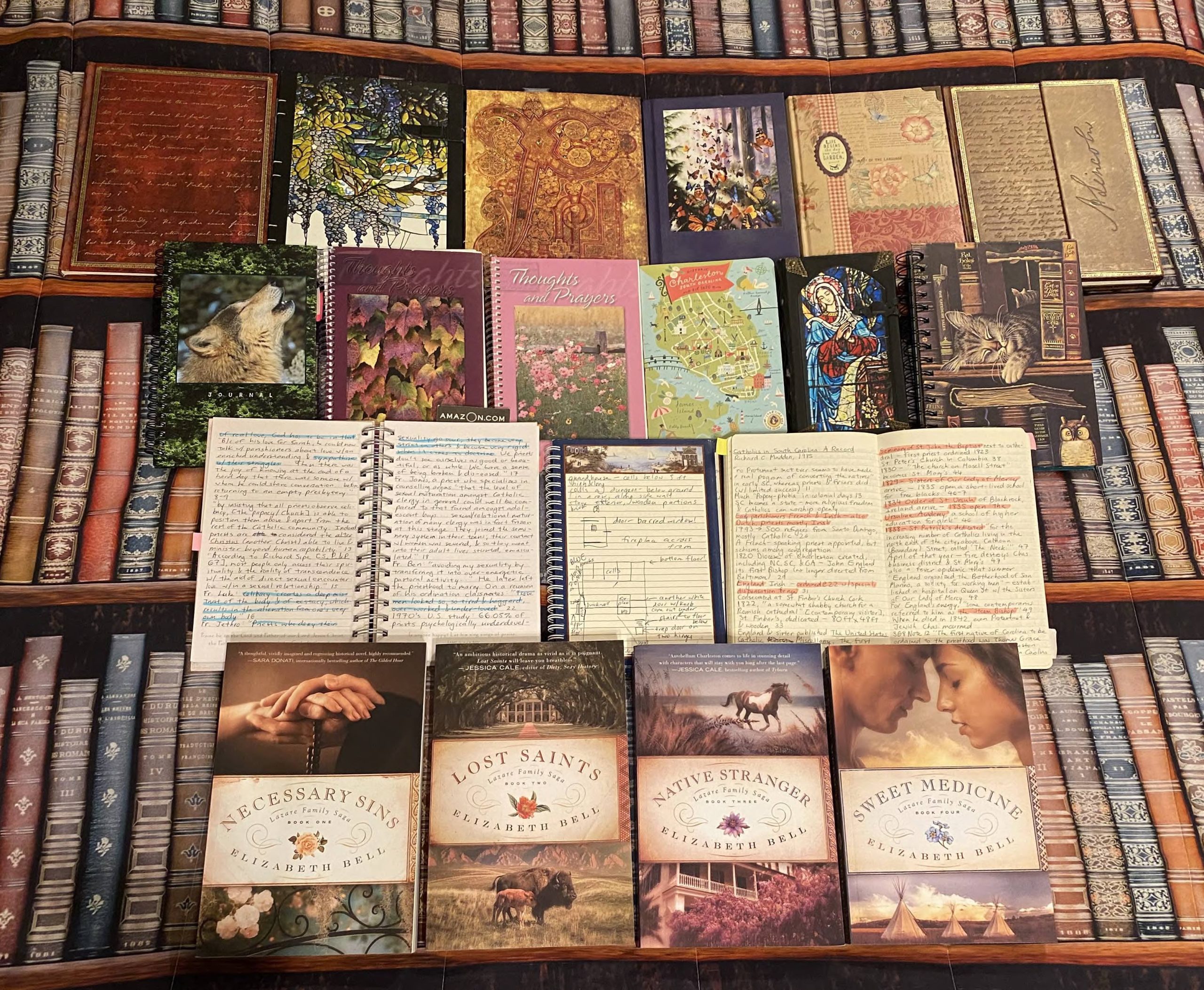

I am a “pantser,” not a plotter. This means I write “by the seat of my pants” and do not use an outline. Back in school, when we were supposed to write an outline for an essay, I’d write the essay first, then the outline. I’ve always hated them! For me, structure strangles creativity instead…

For the Love of Critters

One of my characters, Clare Stratford, is a Southern belle. When she falls in love, however, she considers spending the rest of her life as a Cheyenne Indian. So I knew she couldn’t be prone to “the vapors”; she had to be fearless and in touch with the natural world. Therefore, I gave Clare my…

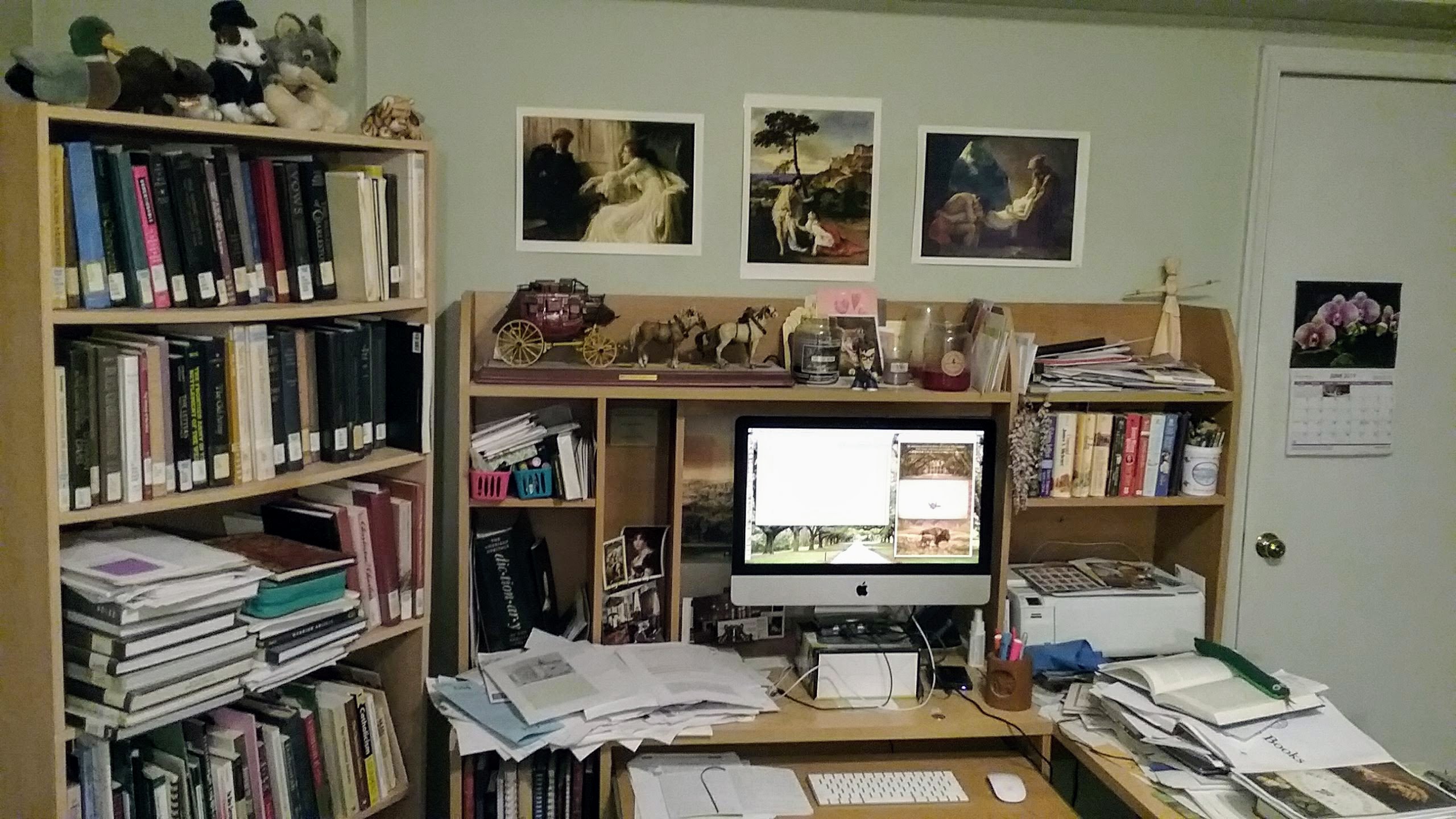

The Art Over My Desk

Above my messy writer’s desk overflowing with research materials, I hung three works of art that helped inspire my historical family saga with strong romantic elements. Let’s take a closer look. Frank Dicksee’s The Confession (1896), a Victorian problem picture with multiple possible meanings. Is the man the woman’s husband or her priest? Which one…

Flashback: The Year It All Began

Over the next few months, I’ll be reviving some of my most substantial, evergreen newsletters as blog posts so that anyone can read them. And so it begins! The year was 1994. Schindler’s List won the Best Picture Oscar. Jeff Bezos founded Amazon. (Remember the days when it sold only books and you got a free bookmark…

My Debt to Colonial Williamsburg

Most of my Lazare Family Saga series takes place in the 19th century, so you might think visits to an 18th-century living history museum wouldn’t be terribly useful to my research. In fact, Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia was one of the richest sources for my fiction set mostly in 19th-century South Carolina. Here’s how! After I moved…

What’s in a (Character) Name?

In Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare famously wrote: What’s in a name? that which we call a roseBy any other name would smell as sweet;So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d,Retain that dear perfection which he owesWithout that title. But he gave those words to a lovestruck teenager. I suspect Shakespeare himself felt differently,…

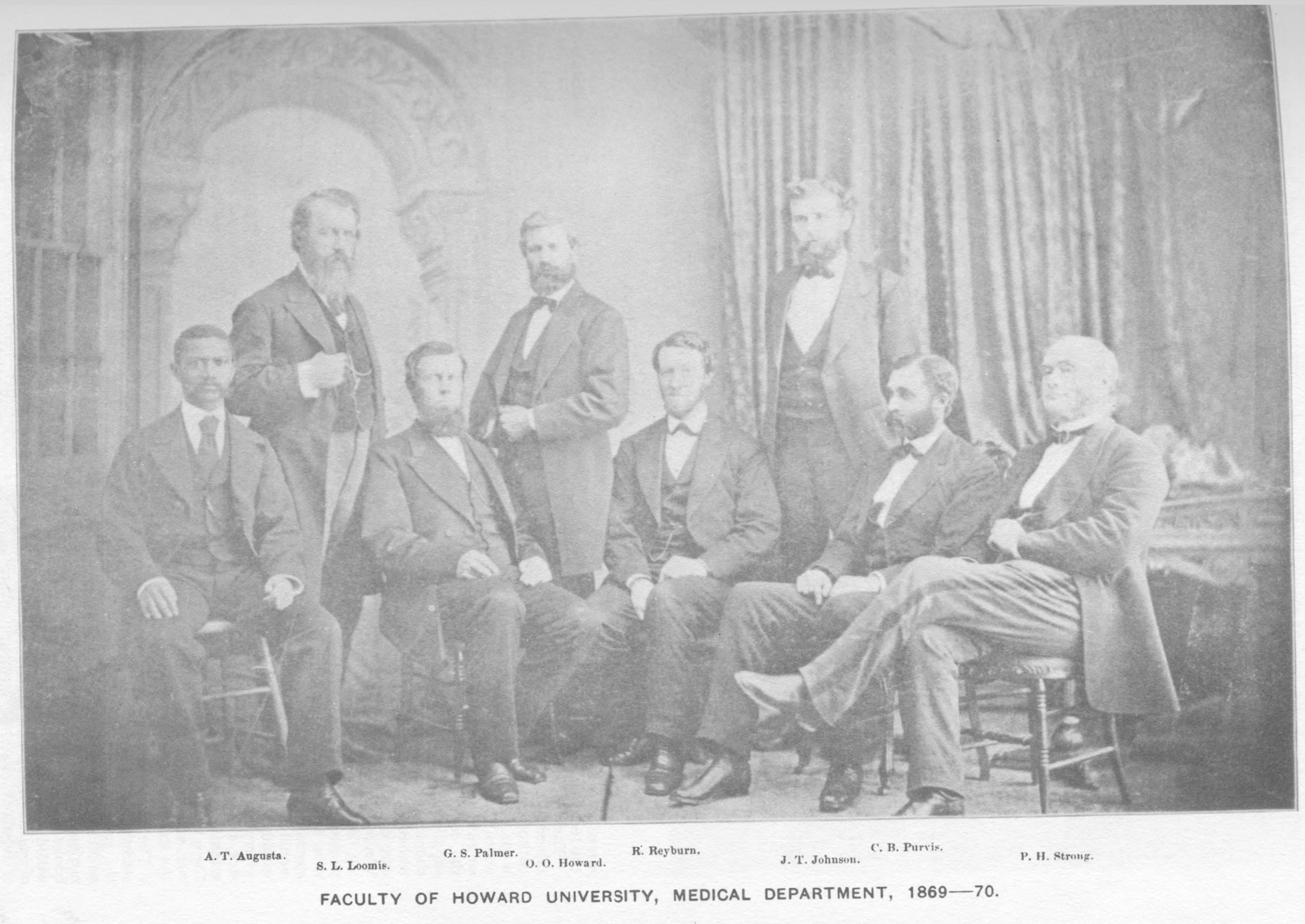

When the Research Rabbit Hole Leads You Back Home

It’s funny how I’ll puzzle over a story problem for months only to realize that the answer has been all but staring me in the face. Although most of my historical series, the Lazare Family Saga, is set in South Carolina and (what is now) Wyoming, I live in Northern Virginia near Washington, D.C. That…

End of content

End of content