When the Research Rabbit Hole Leads You Back Home

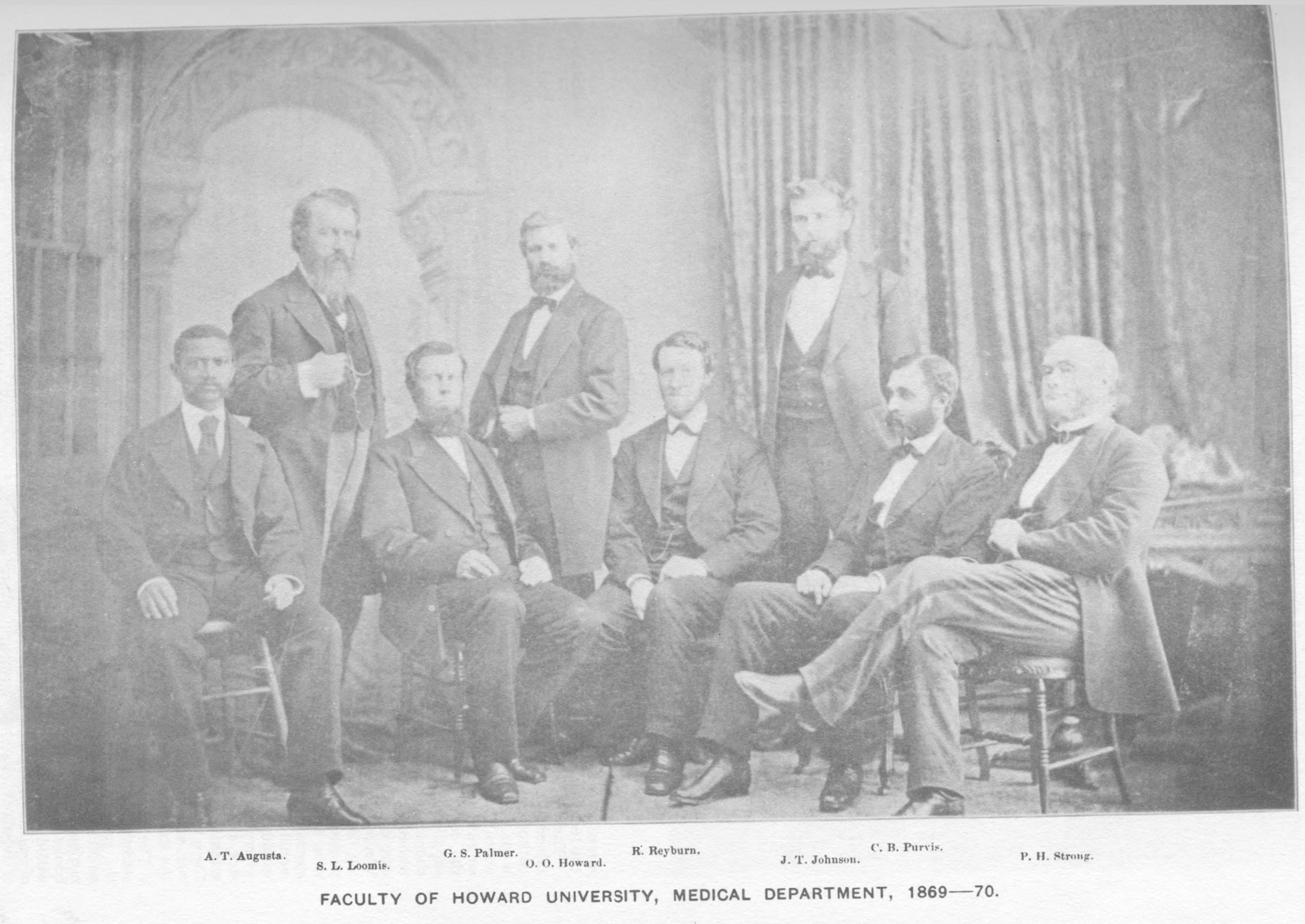

It’s funny how I’ll puzzle over a story problem for months only to realize that the answer has been all but staring me in the face. Although most of my historical series, the Lazare Family Saga, is set in South Carolina and (what is now) Wyoming, I live in Northern Virginia near Washington, D.C. That…

Why Go Indie?

The short answer is: I had no choice. The slightly longer answer: If I hadn’t, you wouldn’t know my novels exist. But let’s back up a moment. You may be asking yourself not why but “what is indie?” It’s a term that’s also used in music and film. “Indie” means “this artwork is independently produced;…

What’s a Claire-Voie?

On the spine and back cover of my paperbacks and on the title page of all my novels, you’ll see my logo above the words “Claire-Voie Books.” What’s a claire-voie, you ask? It’s a gardening term borrowed from French that originated in the 17th century. A claire-voie (pronounced klair-vwah) is a window or opening that…

What’s That Symbol?

You may have wondered about the ornate, round design I use as an avatar. It’s a logo I created to symbolize my historical fiction series, the Lazare Family Saga. I was able to pack a great number of meanings into this design, significance both complementary and conflicting. Paradoxes are at the heart of my work;…

The Importance of Warts

My fellow historical novelist M. K. Tod invited me to write a guest post on her excellent blog A Writer of History. From Colonial Williamsburg to historical novelists, I argue that those interpreting the past should strive for authenticity, even—especially—when it’s not pretty. Or as I like to call it, The Importance of Warts. Read…

What’s Your Genre?

Upmarket. Historical fiction. Family Saga. Mainstream fiction with a central romance. All these terms describe my work, which doesn’t fit neatly into a single category. I see this as a strength. Love beautiful writing tackling profound subjects? You’ll find it in my novels. Love history? I’ll wow you with my research. Love epics about multiple…

My Pen Name

I was born Jennifer Becker, but I have never felt like a Jennifer. In another context, it would have been a lovely name. After all, Jennifer is a form of Guinevere. But in my generation, there were Jennifers everywhere. In high school, I had an advanced-level French class with five students in it—and three of…

End of content

End of content