What’s in a (Character) Name?

In Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare famously wrote:

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes

Without that title.

But he gave those words to a lovestruck teenager. I suspect Shakespeare himself felt differently, that all writers do. Names matter. It matters whether you call someone “a slave” or “an enslaved person.” It matters whether you call a person Zizistas (their name for themselves, which means “the People”) or Cheyenne (another tribe’s name for them, which means “we do not understand their language”). It even matters what you call a rose, as my character Joseph discovers in Lost Saints.

Photo by Nadiatalent

I’ve agonized over the names of every one of my characters. Across the quarter century I spent writing the Lazare Family Saga, I changed their names many times till I found just the right ones. In this post, I’ll share some of the character names I rejected after finding they didn’t fit and explain why I chose the names I did.

In early drafts, Joseph’s relationship with Tessa (Necessary Sins and Lost Saints) was only backstory to David, Clare, and Ésh’s love triangle (Native Stranger and Sweet Medicine). My fictional priest wasn’t yet a point-of-view character. At that time, he wasn’t Joseph and she wasn’t Tessa.

Instead, my priest was named Thierry, a classic French name. I liked the sound of it: TEE-i-ree, with a silent h and lovely rolling r’s. But for a main character, it’s too French; English speakers are sure to mispronounce it. For a while, I switched to Étienne, also sadly too French. Not wanting to lose Thierry or Étienne entirely, I gifted them to more minor characters, Joseph’s relatives.

For my priest, I chose Joseph, naming him after both Biblical men with this name. Old Testament Joseph is enslaved, but his sufferings have a purpose; because of them, he’s able to save his family. He’s also famously chaste. So is New Testament Joseph. In Catholic iconography, Mary’s husband Joseph is often portrayed not as his young wife’s age but as an old man with white hair, reinforcing the Catholic dogma that he and Mary never had a sexual relationship. Not even after Jesus was born. Heaven forbid she should be so “defiled”! No, Saint Joseph is beyond all that. So my character Joseph’s name is a reminder of this impossible standard of “purity.” My Joseph tells himself that God gave him Tessa as He gave Mary to New Testament Joseph—to admire but not to touch. Ever. Really?

Tessa was initially named Aisling (pronounced ASH-ling). I loved the Irish legend behind the name, a legend about a beautiful woman who foretells change the way this mortal woman changes Joseph. Aisling means “vision.” An Irish character should have an Irish name, I thought. Not so fast. As I got deeper into my research, I realized that a good Catholic family like Tessa’s would never give their daughter a pagan name like Aisling. I needed to find a saint’s name. Furthermore, because the British Crown controlled Ireland in the 19th century, Irish people had Anglicized names.

So decided to name Joseph’s beloved after Saint Teresa of Ávila. She’s called Tessa, which sounds softer and more feminine. It also invokes the heroine of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), a work to which I am indebted for some of my themes. Even before he meets Tessa, Joseph has a relationship with Saint Teresa. He marvels at Bernini’s statue of the saint in Rome, and Tessa herself deeply admires her patron saint. I explain why in Necessary Sins.

Photo by Benjamín Núñez González

Until the final few drafts, Tessa’s daughter was named Cara. Her father wanted to name her Carolina after his state. Tessa and everyone who really loved the girl called her Cara, which is both Italian for “dear one” and Irish for “friend.” Perfect, right? But like Aisling, Cara wasn’t Catholic enough. There aren’t any saints named Cara. Her final name, Clare, honors Saint Clare of Assisi. It also honors the beautiful Irish county where Tessa grew up.

David was initially named Donatien (do-nah-TYENH), a French name meaning “gift.” Yep, same root as the English word “donation.” Again, I loved how it rolled off my tongue; but again, it was too French, and English speakers were sure to mispronounce it. When I learned it was the first name of the infamous Marquis de Sade (who is nothing like David), that was the nail in Donatien’s coffin.

Instead, I named Joseph’s nephew for the Biblical King David, whose name means “beloved.” King David sins about as badly as a man can sin. He covets Bathsheba, who’s already married to David’s friend Uriah. So David has Uriah killed to get him out of the way. Yet the Catholic Church canonizes King David as a saint. God not only forgives David, He blesses the fruit of his sin: Bathsheba bears David sons, and their descendants are both New Testament Joseph and the Virgin Mary. Scholars doubt that Bathsheba married her husband’s murderer willingly. So the name David ties into my “necessary sins” theme: it invokes grace and good coming from bad.

With both Cara/Clare and Donatien/David, I kept the first letters of their names the same. Sometimes a letter simply sounds right for a character, so I concentrate on names that start with that letter till I find one that fits.

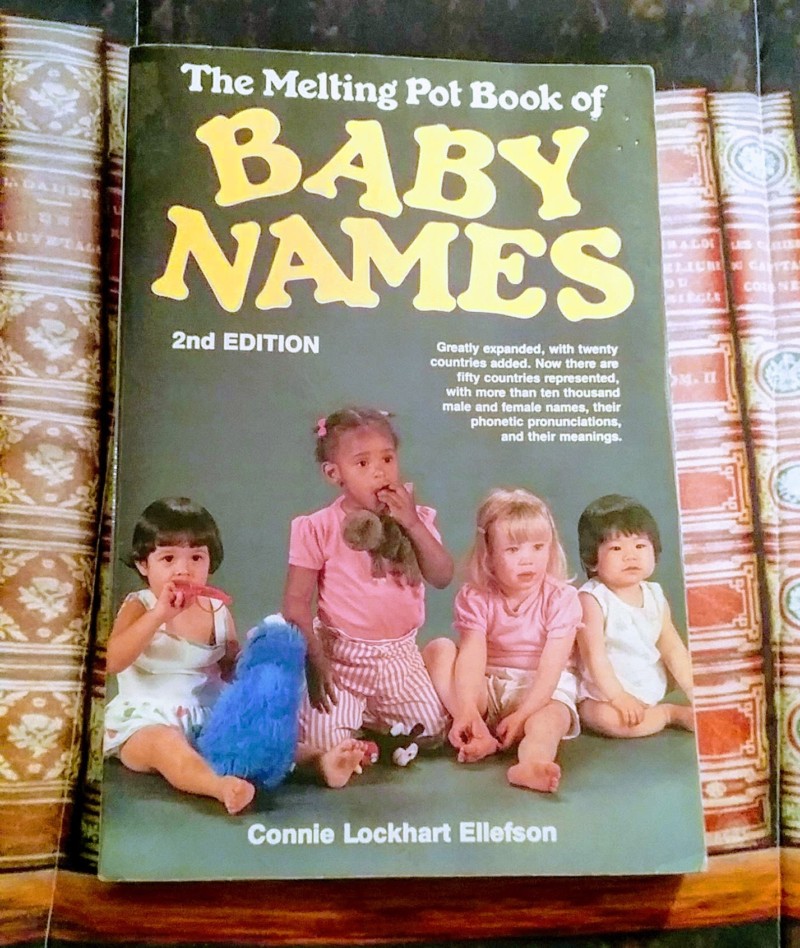

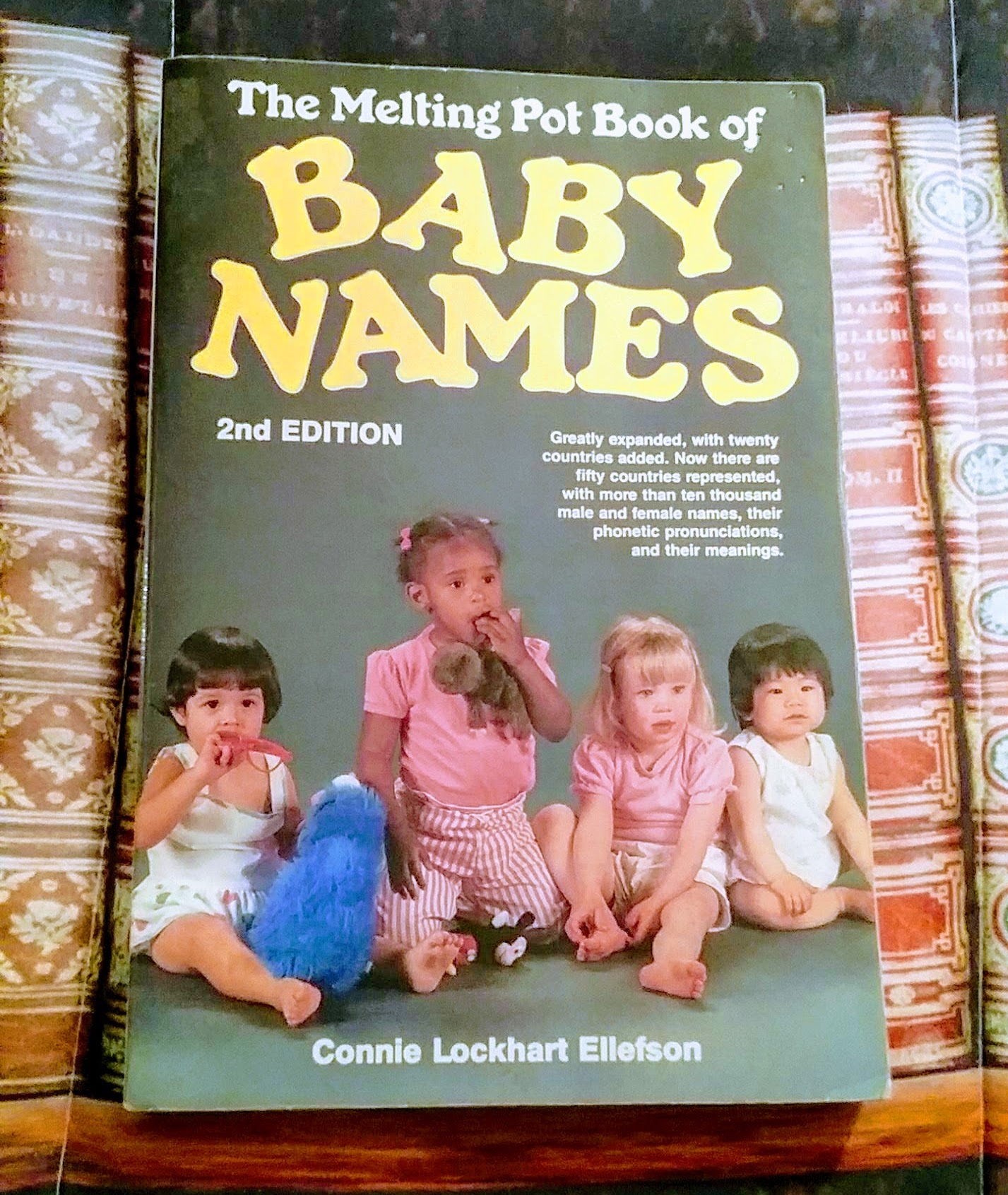

My saga’s fifth major character was initially named Iye. I found this name in Connie Lockhart Ellefson’s The Melting Pot Book of Baby Names, one of many name books I consulted as I pondered what to call my characters. This was before websites like “Behind the Name“—I was researching old school.

This Melting Pot book was my favorite because it organized names by cultures and countries and told me how to pronounce those names. Under the North American Indian section, I found the male name “Iye (EE-yeh): smoke.” It didn’t mention a tribe of origin, but it was close to a Scottish name I wanted to use for this character’s “white” name: Ian.

Yet again, I realized few readers would pronounce this name properly. Even if they did, Iye was a bit too close to Eeyore from “Winnie the Pooh” or the nonsense syllables “E-I-E-I-O” in the nursery rhyme “Old MacDonald Had a Farm.” My work is for adults. My heroine is going to be saying this name in intimate scenes, and nobody should be sniggering.

I sense a pattern here: younger me had a penchant for giving characters exotic-to-me, difficult-for-English-speakers-to-pronounce names. Research, revise, and learn. Bizarre, anachronistic names are a sign of an amateur writer who’s pleasing her own fancy and doesn’t care about authenticity.

Most importantly, this fifth character was Zizistas (Cheyenne); he needed a Zizistas name. I could write a whole post about Zizistas names. To be brief, I settled on Ésh, short and sweet with an appropriate meaning: “sky.” Unlike Zizistas babies, this (mostly) white baby was born with sky-blue eyes.

One of my early readers asked why the name Ésh has an accent over the É. Acute accents (´) usually signify emphasis on a syllable, so monosyllabic words don’t need them. My reader was wise to ask. In fact, the word Ésh has two syllables, but I’ve elided one (omitted it). The word should properly be spelled Éshe. The Zizistas language has whispered syllables, meaning that final e is almost but not quite silent, like a breath. I thought leaving it off aided with pronunciation, so that readers wouldn’t say “Esh-eh” or “Eh-shee” in their heads. I retained the accent mark because I thought “Esh” looked less foreign and had less dignity. To my Charleston characters, Ésh is an “other.” His thought processes are different than theirs. He’s the primary “native stranger” of Book 3’s title, and I wanted his name to reflect that.

You’ll notice I’ve been purposefully vague about who Ésh actually is. If you want to find out, you’ll have to read my saga. 😉

Very thoughtful explanation of your character names. I remember all the previous iterations and evolutions. Wish I could have consulted with you about your own birth name.

Only authors know what their (fictional) children will be like and can name them appropriately! Even then, it takes some experimentation!