When the Research Rabbit Hole Leads You Back Home

It’s funny how I’ll puzzle over a story problem for months only to realize that the answer has been all but staring me in the face. Although most of my historical series, the Lazare Family Saga, is set in South Carolina and (what is now) Wyoming, I live in Northern Virginia near Washington, D.C. That will soon be relevant. Journey down the research rabbit hole with me…

The Lazare Family Saga grapples with racism and slavery in the antebellum American South. Sweet Medicine, the fourth and final book, takes the characters into the Reconstruction era after the Civil War. I had to figure out what the Lazare family should be doing during this momentous period in American history, something that would make a fitting capstone to my saga and “bring it all together.”

The title of Book 4, Sweet Medicine, has multiple meanings. One of these is literal: two Lazares are medical doctors. Another meaning is figurative, referring to spiritual healing. For one particular character (I’m being deliberately vague to minimize spoilers), I wanted his Reconstruction choices to encompass both literal and figurative healing. Although he is a physician dedicated to helping others, he is himself psychologically wounded.

I wanted this character to be involved in educating newly freed African-Americans as a way of reclaiming his ancestry and healing his fractured identity, since the Lazares are a multiracial family who have been “passing” as white for most of the series. Before Emancipation, penalties for teaching an enslaved person to read included imprisonment and hefty fines. An enslaved person caught with a book would be whipped and often sold because his/her master considered an educated slave dangerous. Both during and after slavery, when an African-American learned to read, it was a way of declaring his/her personhood, of declaring that (s)he was worthy of more than manual labor. During Reconstruction, whole families—from children to grandparents—eagerly attended classes. After the devastation of slavery, education provided a means for African-Americans to heal themselves spiritually. White supremacists understood the symbolic and practical importance of education and frequently targeted schools and teachers.

But how could I pair this pro-education idea with literal medicine? The Reconstruction part of my story appears as an Epilogue. I don’t have fully fleshed out scenes to go into great detail. My characters’ Reconstruction choices must pack a satisfying emotional punch within a few paragraphs. Since the character in question commits a felony in South Carolina earlier in Sweet Medicine, I had to keep him away from that state. Beyond this limitation, the possibilities were mind-boggling. This is the part of historical fiction where the author conducts much more research than she’ll ever use, because she needs to eliminate possibilities.

At first, I placed my character at Hampton Institute. Today, this is Hampton University, located in my adopted state of Virginia but a solid 2.5 hour drive from me. I liked that enslaved people first escaped to Union lines near Hampton. I liked that Hampton University continues to thrive today, one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities a.k.a. HBCU (meaning their student bodies are primarily African-American). But there was no medical connection with Hampton.

Another central subject in my work is Native Americans. They too were educated at Hampton, which would seem to be a vote in its favor. However, Hampton was one of the colleges where the white teachers sought to “kill the Indian, and save the man”—in other words, to strip the Native students of their culture.

Even with its black students, Hampton focused on vocational and agricultural degrees. This was actually called “the Hampton Idea.” Instead of being offered a “higher education,” students were trained to do manual labor because many white people thought freedmen were not (yet) intellectually capable of more cerebral careers. Even black people like Booker T. Washington advocated the Hampton Idea, which argued that African-Americans should “stay in their place,” accept racial segregation, and not expect to become social equals with white people. By placing my character at Hampton Institute, I felt I would be endorsing harmful prejudices.

So where should I place my character during Reconstruction? As it turns out, I have lived near the solution for over a decade and have borrowed books from its library many times: Howard University in Washington, D.C. I knew Howard was also one of the HBCU. I vaguely knew it was founded just after the Civil War (1867). But I didn’t realize how special Howard was.

Howard consisted of multiple colleges from the beginning: law, theology, normal (for training teachers), and medicine. Its founders understood that given an equal chance, African-Americans are every bit as capable of succeeding in intellectual professions as white people.

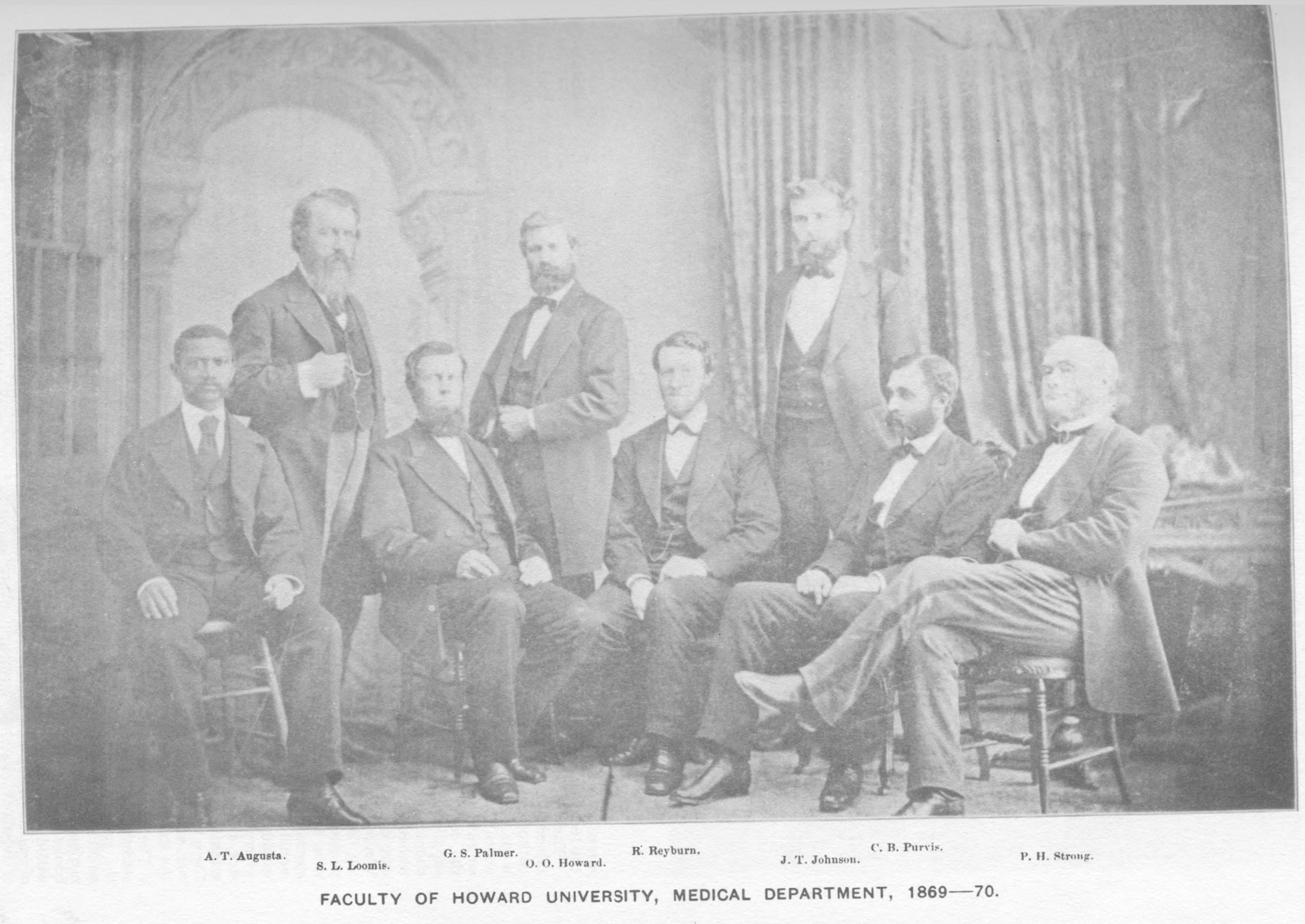

Not only that, Howard’s advanced curriculum was open to all races and both sexes from its 1867 founding. Howard admitted at least a few Native American students. Two of its medical professors in the 1870s were men of color, and one professor was a white woman. The #1 fear of white supremacists is black men intermingling with white women—and that very “amalgamation” was happening at Howard during Reconstruction.

Considering the segregation to come, Howard University circa 1870 was ahead of its time and Too Awesome Not to Use. Eureka! I’d found the perfect capstone to my family saga—practically in my own backyard.

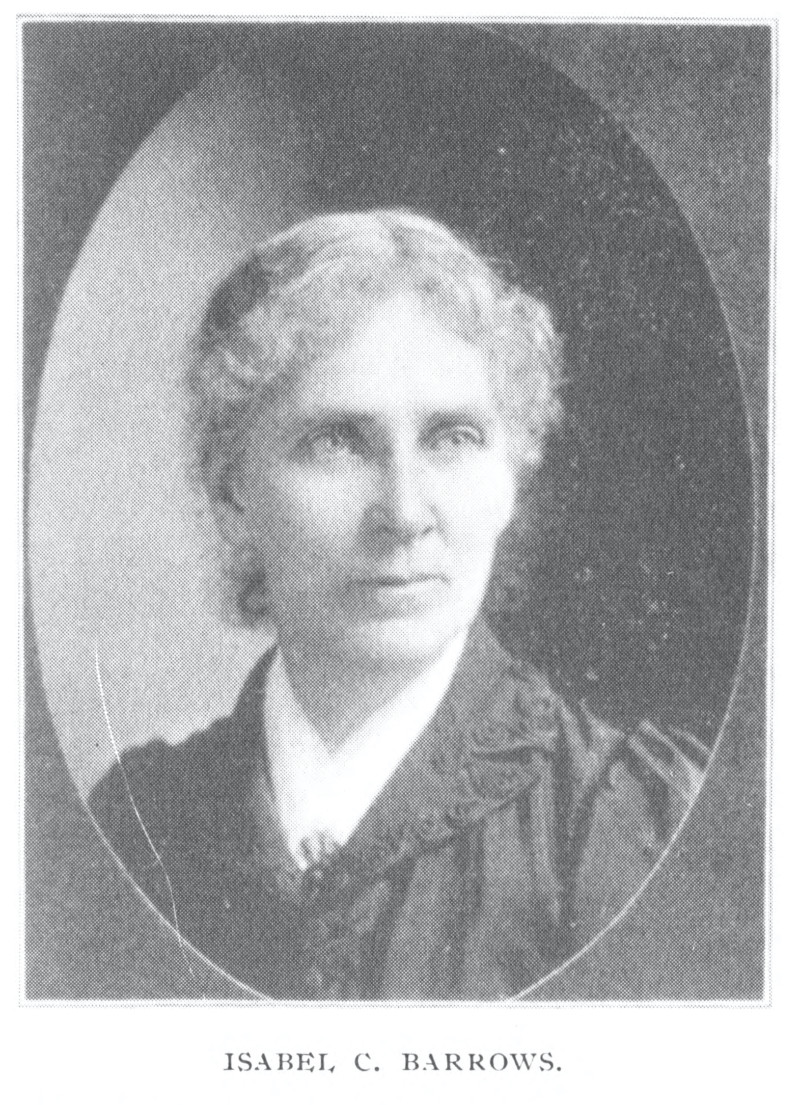

Dr. Isabel C. Barrows earned her degree at Woman’s Medical College of New York City in 1869 and also studied in Vienna, Austria. She was a professor in Howard University’s Medical Department from 1870-1873 (a year too late to appear in the below group photo). She specialized in diseases of the eye and ear.

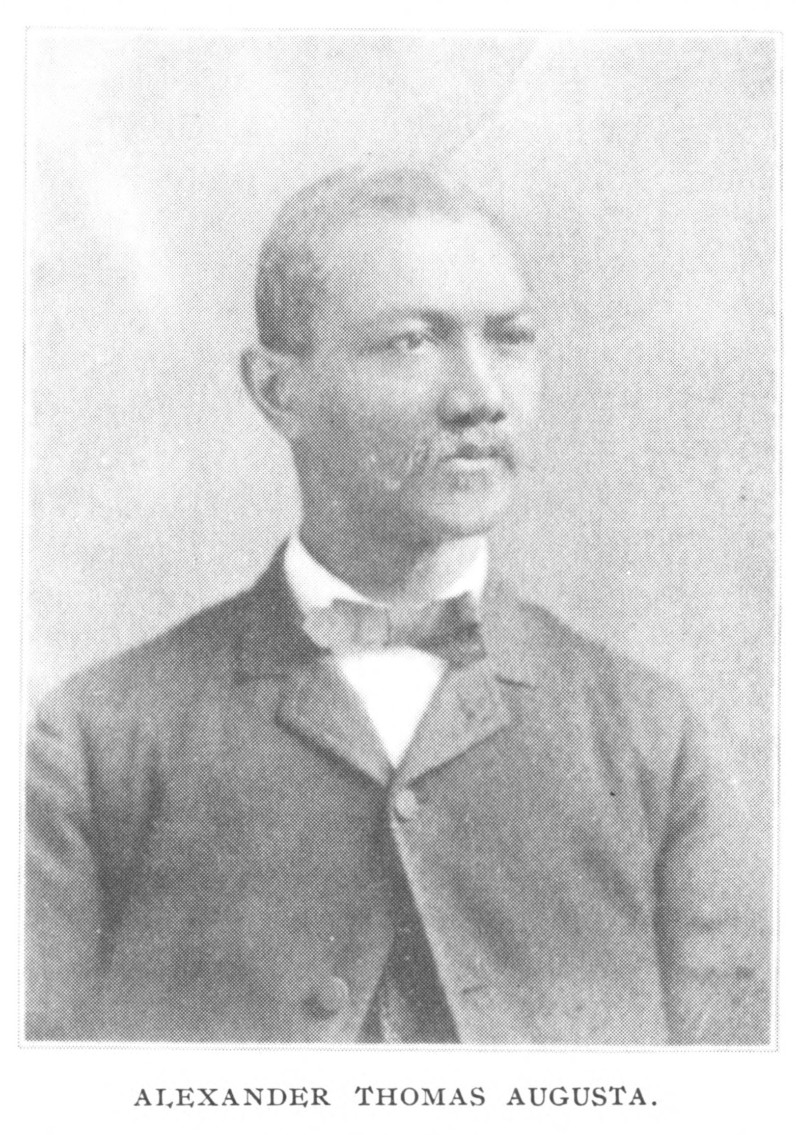

Dr. Alexander T. Augusta was born to free black parents in Norfolk, Virginia. He earned his degree at Trinity Medical College in Toronto, Canada in 1856. He was the first black medical officer during the Civil War, commissioned as a major and appointed head surgeon of the 7th U.S. Colored Infantry. Dr. Augusta was also the first black hospital administrator in the United States; the first black medical professor, teaching at Howard from 1869-1877; and the first black officer buried at Arlington National Cemetery (1890). You can see a photograph of him looking dashing in his Union uniform here.

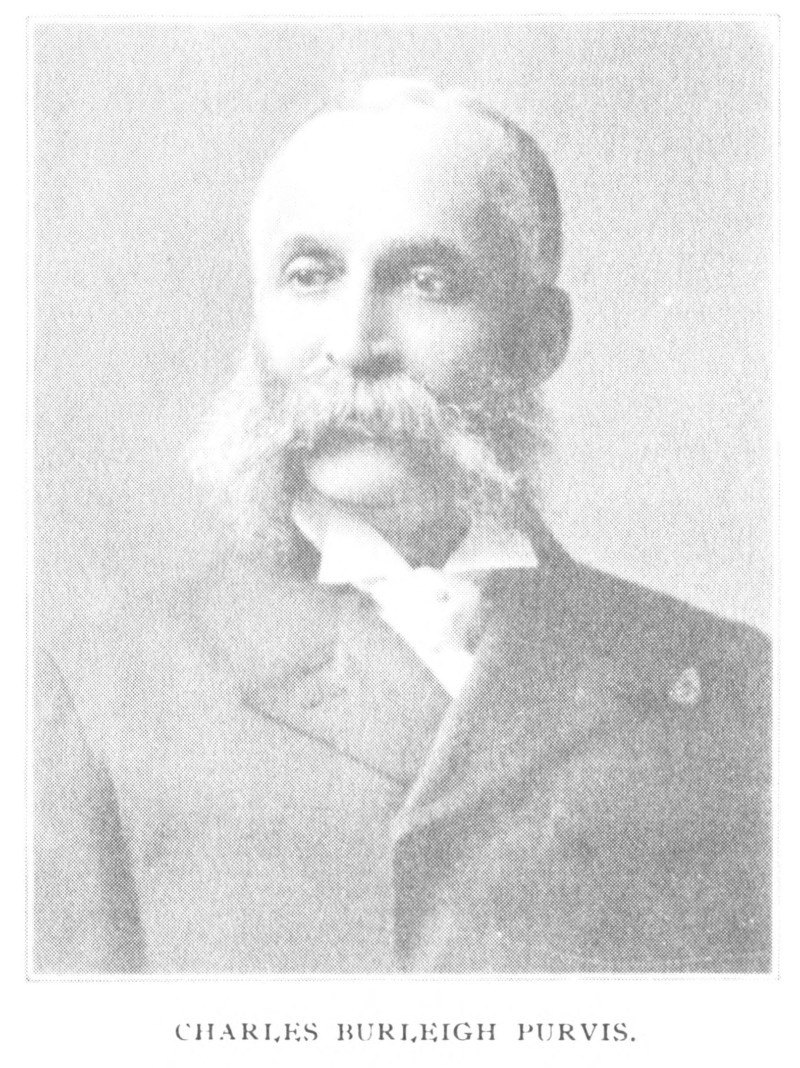

Dr. Charles B. Purvis was born to free black abolitionists in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He served as both a nurse and a surgeon during the Civil War and earned his degree at Wooster Medical College in 1865. Dr. Purvis was a professor in Howard’s Medical Department from 1869-1907. After the Financial Panic of 1873, the university was in dire straights and could no longer pay its faculty. Dr. Purvis continued teaching without a salary for three decades because he believed in Howard’s mission. Without him, the medical school probably would not have survived.

You’ll notice from these photographs that Dr. Purvis could have passed as white. He identified as black and was refused admittance to the American Medical Association because of it. Dr. Purvis’s father, Robert Purvis, was born in Charleston, South Carolina and was active in the Underground Railroad. Finding him was another lovely “full circle” moment in my research, a real-life echo of my fictional Lazare family.

All images in this post taken from the book Howard University Medical Department: A Historical, Biographical, and Statistical Souvenir by Dr. Daniel Smith Lamb, published in 1900. You can view the book in its entirety here: https://dh.howard.edu/med_pub/1

For the history of Howard as a whole, check out Howard University: the First Hundred Years, 1867-1967 by Ralph W. Logan, published in 1969.